American Larch Tree

AMERICAN LARCH

AMERICAN LARCHLarix Americana

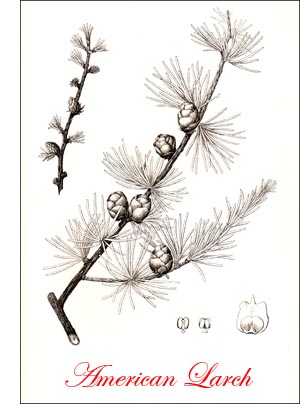

The American Larch, known very generally in New England by the aboriginal name of hacmatack, is not often, in this State, a tall tree. In deep forests it sometimes attains the elevation of 70 feet, but does not usually exceed half that height. It is distinguishes from all others of the family by its crowded tufts of deciduous leaves; from the European larch, by the smallness of its cones and the shortness of its leaves.

It has a straight, erect, rapidly-tapering trunk, clothed with a bluish gray bark, rather rough, with small roundish scales. The branches are numerous, very irregular, and horizontal, or nearly so. The recent shoots, which are very slender, have a grayish red bark, which on older branches becomes brown, and, finally, as on the trunk, blue gray.

The leaves are an inch long, in circular tufts round a central bud, except on the growing shoots, where they are alternate. They are linear, flattened, obscurely four-sided, sessile, and obtusely pointed at the end, of an agreeable light bluish green, and differ from those of all the other cone-bearing trees by the delicacy of their texture. Late in autumn they turn to a soft, leather yellow color, and, in the first days of -November, fall.

The sterile flowers are in solitary, erect catkins, which take the place of the fascicles of leaves towards the ends of the branches; they are nearly round, one-fourth of an inch long, and composed of rounded, yellow anthers, closely arranged. The fertile flowers are in erect, solitary catkins, about the middle of the branches, half an inch long, and made tip of a few floral leaves or scales. Around the base of the catkins are other scales, resembling leaves half transformed, by a dilated wing on each side, into fertile scales. The true scales have a projecting point when in flower, but afterwards become nearly circular, slightly bent in at the edge, and have, within each, two seeds with a scaly wing; the scales and wings are of a pleasant crimson red. The flowering season is May.

The range of the hacmatack is from the mountains of Virginia to Hudson's Bay. At Point Lake, in latitude 65 degrees, it attains, according to Dr. Richardson, to the height of only 6 to 8 feet. It is found in cold swamps in most parts of this State ; but attains its greatest perfection in a region considerably farther to the north.

The wood of the larch is very close-brained and compact, of a reddish or gray color, and remarkable for its weight, and its great strength and durability. In these respects, it is superior to all the other pines, and is surpassed only by the oak. Its durability is even superior to the oak itself ; and in old vessels, the timbers made of hacmatack have been found entirely sound, when those of white oak were completely decayed. On these accounts, it is preferred before all other woods, for knees, for beams, and for top timbers. The shipbuilders make two varieties of the wood, the gray and the red, of which the latter is considered best. Its great hardness makes it valuable for steps in exposed situations ; and its compactness gives it great power of resisting the action of fire, and renders it nearly incombustible, except when splintered. It would be Letter than any other wood in buildings intended to be fire-proof.

On account of the very valuable qualities of the wood, the hacmatack would deserve to be extensively cultivated; and there are thousands of acres of cold and swampy land, where it was found naturally, which are now unproductive, and which might be clothed with it. It has, however, been found to be far inferior in rapidity of growth to the European larch, which very- nearly resembles it in appearance, and in the excellent qualities of its wood. This, therefore, should be preferred, as likely to produce, in the same time, a larger quantity of timber from the same surface and at the same expense.

On favorable soils, the European larch is fit for every useful purpose in forty years' growth. Its annual rate of increase in Scotland Las been found to be from one to one and a half inches in circumference at six feet from the ground, on trunks from ten to fifty years of age. It has, moreover, the property of flourishing on surfaces almost without soil, thickly strown with fragments of rocks, on the high and bleak sides and tops of hills, where vegetation scarcely exists. It was in such situations as this, of a description which answers but too well to many waste spots in Massachusetts, that the most successful experiments were made in Scotland by the Dukes of Athol. These are so interesting in themselves, and so deserving of imitation, that a brief account of them cannot be considered unacceptable or out of place here.

The estates of the Dukes of Athol are in the north of Scotland, in the latitude of nearly 57° north. Between 1740 and 1750, James, Duke of Athol, planted more than twelve hundred larch-trees, in various situations and elevations, for the purpose of trying a species of tree then new in Scotland. In 1759, he "planted seven hundred larches over a space of twenty-nine Scotch acres, intermixed with other kinds of forest-trees, with the view of trying the value of the larch as a timber tree. This plantation extended up the face of a hill from two hundred to four hundred feet above the level of the sea. The rocky ground of which it was composed was covered with loose and crumbling masses of mica slate, and was not worth above 3 pounds a year altogether."

His successor, John, Duke of Athol, "first conceived the idea of planting larch by itself as a forest-tree, and of planting the sides of the hills about Dunkeld." He planted three acres with larches alone, at an elevation of five or six hundred feet above the level of the sea, on soil not worth a shilling an acre. His son, Duke John, continuing the execution of his father's plans, had planted, in 1783), two hundred and seventy-nine thousand trees.

Observing the rapid growth and hardy nature of the larch, he determined to cover with it the steep acclivities of mountains of greater altitude than any that had yet been tried. He therefore enclosed a space of twenty-nine acres, "on the rugged summit of Craig-y-barns, and planted a strip entirely with larches, among the crevices and hollows of the rocks, where the least soil could be found. At this elevation, none of the larger kinds of natural plants grew, so that the grounds required no previous preparation of clearing." This plantation was formed in 1785 and 1786. Between that year and 1791, he planted six hundred and eighty acres with five hundred thousand larches, the greater part only sprinkled over the surface, on account of the difficulty of procuring a sufficient number of plants.

"Observing with satisfaction and admiration the luxuriant growth of the larch in all situations, and its hardihood, even in the most exposed regions, the duke resolved on pushing entire larch plantations still farther, to the summit of the highest hills." He therefore determined to cover with larch sixteen hundred Scotch acres, "situated from nine hundred to twelve hundred feet above the level of the sea."

These, with four hundred acres more, occupied from 1800 to 1815. Having now no doubt whatever of the successful growth of the larch in very elevated situations, the duke still farther pursued his object of covering all his mountainous regions with that valuable wood. Accordingly, a space to the northward of the one last described, containing 2,959 Scotch acres, was immediately enclosed, and planted entirely with larch.

"The planting of this forest appears to have terminated the labors of the duke in planting." He and his predecessors had planted more than fourteen millions of larch plants, occupying over ten thousand English acres. It has been estimated, that the whole forest on mountain ground, planted entirely with larch, about six thousand five hundred Scotch acres, will, in seventy-two years from the time of planting, be a forest of timber fit for building the largest ships.

The effect upon the land in improving it for pasturage is very important. If the larch-trees are planted close, they will choke the bushes and natural grasses. This may be effected in ten or fifteen years. After this, gradual thinnings may be accompanied by the introduction of all the most valuable cultivated grasses, which, under the cover of the larches, will flourish "with the foliage possessing a softness and luxuriance not possessed in other situations." Vast sums have been realized by the successor of this duke from his plantations on the Scotch mountains.

There are large surfaces, particularly in Essex and Bristol counties, of bleak, rocky, barren hills, or wet plains, not so exposed as that spoken of above, but almost equally useless, which might doubtless be redeemed by a similar process. We have now to send to the Southern States, and to New York and Maine, for a great portion of our ship timber. Of this the live oak and white oak alone are superior to larch, and for many purposes they are only equal to it.

In seventy years, the ship-yards on Mystic River, and on Buzzard's Bay, might be supplied with timber from the neighboring shores, if the land suitable for that purpose, and for little else, were immediately to be planted with larch. In half that space of time, the thinnings of the forest would furnish the smaller timber in abundance. It may safely be predicted, that, if measures are not taken to restore or preserve our forests, if the same waste goes on which has gone on for the last fifty years, in seventy years timber of every kind will be as rare and as dear in New England as it now is in Scotland.

On the continent of Europe, the larch is put to a great variety of uses. It is considered the best of the woods, both for the carpenter and the joiner. Casks are made of it, nearly incorruptible ; water-pipes, shingles, vine-props. Its excellent properties for ship-building, as enumerated by Pontey, are its freedom from knots, its durability, its little liability to shrink or to crack, its toughness, its beautiful color, its capability to receive polish, and its incorruptibility when exposed to alternations of moisture and dryness.

The soils suitable for the larch, according to Matthew, are sound rock, with a covering f loam, particularly when the rock is jagged or cleft; gravel, not ferruginous, in which water does not stagnate, even though nearly bare of vegetable mould; firm, dry clays, and sound, brown loam; all very rough ground, particularly ravines. The most desirable situation is where the roots will neither be drowned by stagnant water in winter, nor parched by drought in summer.

American Larch Tree picture