Sweet Gum Tree

Genus LIQUIDAMBAR, Linn.

Genus LIQUIDAMBAR, Linn.The Sweet Gum (Liquidambar Styraciflua, Linn.)-A large tree 75 to 140 feet high, with straight trunk and short, slender branches, forming a pyramidal or oblong head. Bark reddish brown, furrowed, scaly, on old trunks; on young trees, ashy grey, with hard, warty excrescences; twigs, pale, usually with corky wings, which continue to grow for years. Wood bright reddish brown, striped with black, straight, close grained, lustrous when polished, hard, heavy, not strong. Buds acute, reddish and hairy at tips, small.

Leaves 5 to 7 inches, long and broadly cleft into 5, rarely 7, triangular-pointed lobes, which are finely saw-toothed; with resinous sap, lustrous when mature, streaked crimson, and yellow in autumn. Flowers after leaves, monoecious; staminate in terminal, hairy racemes, 2 to 3 inches long, set with head-like stamen clusters; pistillate in solitary swinging balls from axils of upper leaves; stigmas conspicuously twisted. Fruits dry, swinging balls, 1 1/2 inches in diameter, of the hardened, 2-horned capsules. Single seed, winged, 2 inch long in some cells.

Most of the cells filled with minute, aborted seeds. Preferred habitat, low wet woodlands. Distribution, Connecticut to Missouri; south to Florida and Texas; also in Mexico and Central America. Uses: Valuable ornamental and shade trees. Lumber used for railroad ties, paving blocks, shingles, fruit boxes, spools; choice pieces known as "satin walnut," used for veneering, furniture and for interior finishing of houses. Dyed black, it imitates ebony, in picture frames and cabinet work.

The sweet gum is probably more closely linked with plantation life in the South than any other tree. It grows in the swamps, and many a slave hugged the slender shaft of a leafy gum tree while he waited all day for the north star to point him the way to freedom. Here the 'possum and the 'coon found similar refuge from hunters and their dogs; and it was a hollow gum tree that old "Nicodemus, the slave," was buried in to be waked in time for the great jubilee!

As a child, I lived in a state north of the range of the most intrepid liquidambar tree. I recall with great vividness an old ex-slave's description and eulogy of the tree, and the song he sang, full of the exaltation his clearly bought freedom always roused in him-especially the thrilling chorus:

" Da's a good time comin', 'tis almos' heal,

Hit's bin long, long on de way:

Run 'n' tell 'Lijah t' hurry up, Pomp',

Meet us at de gum tree, down in de swamp;

Wake Nicodemus to-day!"

Travellers in the bayou country of the Mississippi Valley can easily verify the statement that a hollow gum tree is large enough to entomb a man. Giants exist there to-day, standing in rich bottom lands, or on soil that is inundated a part of the year, whose trunks, 15 feet or more in girth, carry their tops 15c feet into the air. These trees, often bare of branches for half their height, look like great columns set amid the tropical vegetation, and towering high above most of their neighbour trees. In it's northern range the tree sacrifices size but not beauty.

It is good to take a whole year to get acquainted with the sweet gum, and it doesn't really matter when one begins. The seed balls swing on the trees in winter, looking like the buttonballs of the sycamore. A second glance shows the paired "cows' horns" above the gaping pods, and the crowded, undeveloped seeds shake out like sawdust. An easier way to identify the tree is by the narrow blade-like ridges of bark that in most cases adorn the twigs. Strangely, these are on the upper side of horizontal twigs, and all around the vertical ones. The shading of olives and greys and browns in these corky ridges reminds one of the banding of an agate. Now and then you come upon a gum tree whose twigs are all smooth.

Farther down, the branches have warty bark, broken into rough, horny plates. This gives the tree its name, "alligatorwood." Then the grey of the big branches gives way to the redbrown of the trunk; the shallow fissures and scaly ridges give a finer texture to this oldest bark than the limbs give us reason to expect.

In summer time the leaves of the sweet gum are our sure guide to its identity. "Star-leaved gum," it is often called. There is no other tree whose leaf so closely resembles a regular, six-pointed star with one point missing where the petiole is fastened on. These leaf stems are long and flexible-a very important fact in analysing the beauty of the sweet gum tree in full leaf. The large shining blades flutter on their stems,

"Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle in the Milky Way."

They fairly dazzle the beholder, as the polished leaves of the tulip tree always do.

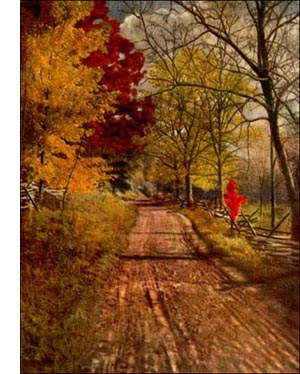

But the summer garb of the sweet gum tree is pale and monotonous compared with the radiant beauty of its October foliage. Wherever gum trees grow, there the autumn landscape is painted with the changeful splendour of sunset skies. The leaves do not seem to dry and wither as maples and dogwoods do. They give up their bright green for the most gorgeous shades of red. "The tree is not a flame-it is a conflagration!"

Often one sees a fence-row thicket of young gum trees all burning low with dull crimsons as if their fires sullenly smoulder, and might at any moment burst into the clear orange-red flame that consumes a neighbour tree. Afterward, the foliage may turn to those browns and lilac tones assumed by ash trees, but as a rule the ground is littered with the leaves before they fadethey "die like the dolphin."

The sap of the sweet gum is resinous and fragrant. It is easy to find this out by crushing a leaf or bruising a twig. Chip through the bark of a tree and an aromatic gum accumulates in the wound. In the Northern States this exudation is scant, but it becomes more plentiful as one proceeds south. The most copious flow is from trees in Central America. This gum is known to commerce as "copalm balm," large quantities of which are shipped to Europe from New Orleans and from Mexican ports each year. A Spanish explorer in Mexico described in 1651 "large trees that exude a gum like liquid amber." This was the beginning of the trade. Linnaeus later gave the name "liquidambar" to the whole genus, which contains four species.

Besides our American tree there is a species in eastern Asia, not yet well known, and a very important species, L. orientalis, which forms forests in Asia Minor. Long before the Christian era the fragrant gum storax, or styrax, of these trees was used as incense in the temples of various oriental religions. Later it had its place also with frankincense and myrrh in the censers of the Greek and Roman Catholic churches. It was used then, as it is now, as a healing balm, as a medicinal drug and as a perfume.

The American gum is believed to have the same properties as the oriental storax, and it is manufactured into medicines, perfumes, and incense. As a dry gum, it is the standard glove perfume in France.

First and last, it is not the products of the sweet gum tree that should first commend it to the American people. It is the tree itself, beautifying by its growth the landscape of which it is a part. More and more we are realising the value of native things in landscape gardening. There is a lesson for the American (who would not learn it at home) as he hunts in European gardens and nurseries for trees to plant on his estate. Among the finest and most valued trees abroad is his own native Liquidambar Styraciflua, all the more esteemed because there is no European species.

The name "gum tree" is also applied to our tupelos, and to certain species of Eucalyptus, natives of Australia.