Sour Gum or Black Gum Tree

Tupelo, Pepperidge, Sour or Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica, Marsh.)-A medium-sized tree of variable shape, 50 to 100 feet high, with short, rigid, twiggy, horizontal branches. Bark rough, dark grey, broken into many-sided plates; on younger trees, pale brown or grey; branches brown; twigs green to orange, often downy.

Tupelo, Pepperidge, Sour or Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica, Marsh.)-A medium-sized tree of variable shape, 50 to 100 feet high, with short, rigid, twiggy, horizontal branches. Bark rough, dark grey, broken into many-sided plates; on younger trees, pale brown or grey; branches brown; twigs green to orange, often downy. Wood heavy, tough, cross grained, soft, not durable in contact with the soil, hard to work. Buds small, brown, with hairy scales. Leaves alternate, entire, 2 to 4 inches long, oval, leathery, shining above, pale, often hairy beneath, turning scarlet above in autumn.

Flowers, May, after leaves, yellowish green, inconspicuous, polygamo-dioecious; staminate in loose, pendant heads; pistillate larger, 2 or more in a cluster. Fruits, October, 1 to 3 in cluster; fleshy drupes ovoid, blue-black, sour, 2/3 inch long; stone ridged.

Preferred habitat, low, wet soil, borders of swamps, rivers and ponds. Distribution, Maine to Florida; west to southern Ontario, Michigan, Missouri and Texas. Uses: Handsome, hardy ornamental trees. Wood used for mauls, pulleys, hubs, rollers, ox yokes and woodenware.

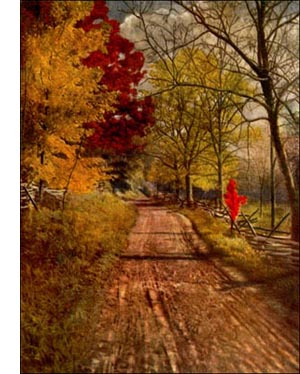

In early fall the rambler in the woods is often startled to see on the mossy carpet in front of him a thick, shining leaf, part of which is still deep green and part as red as blood. It is the tupelo's signal that winter is on the way.

Look up, my friend, and the branches above show only a few leaves coloured like the one you found. Come again in a week or two and the tree is ablaze with reds of every shade. It is a pillar of fire, indeed, among the yellowing ashes and hickories; only the reds of the swamp maples and sumachs compare with it in brilliancy. Who can fail to know the tupelo in the glory of its dying foliage? Certainly no rational being, if he has eyes in his head, and the tree in his neighbourhood.

The sight of one, and a few sprays of its lustrous leaves to put up behind the picture frames at home, are well worth a Sabbath day's journey.

"Tupelo" is the pretty Indian name. "Pepperidge" cannot be accounted for. It is probable that the fiery foliage first led people to suppose this tree to be a relative of the sweet gum. They grow together-both large trees in the bottom lands of the South. This "black gum" can be readily distinguished from the red gum, or liquidambar, as far as the colour of the trunks can be made out. The name, "sour gum," refers to the fruit. Linnaeus gave to this water-loving genus the name of Nyssa, the water nymph who reared the infant Bacchus. It was the fashion for the old botanists to give new plants names derived from classical mythology, without much thought of appropriateness.

The foliage of the tupelo is without question its chiefest charm, but there are others which the leaves partially conceal. The winter aspect of the tree is strikingly picturesque. There is a central axis, such as we see commonly among evergreens but seldom among broad-leaved trees. From this tapering shaft the slender branches spread in level platforms that subdivide into wiry, angular branchlets and end in a dense, flat twig system. A young tupelo in winter has as much rigidity of mien as a young honey locust.

With advancing years the tupelo loses the symmetry of its youth. The lower branches droop dejectedly. The top is likely to die. When the wreck blows over it often shows a hollow butt, for the wood, though tough, is soft and quick to decay. Where the vitality of the tree is low, agencies of deterioration are quick to follow up their advantage. Wood-destroying fungi in the soil rot the trunk off in an incredibly short time. An artist studying the expression of trees in winter will look in vain for a more melancholy figure than an aged tupelo, smitten by untoward fates-the very King Lear of the forest.

In the ponds of the pine barrens in the Carolinas a twoflowered tupelo is found, variety biflora. It is smaller than the parent species, and has a much swollen base, with large roots that hump themselves out of the water. Its leaves are smaller than those the tupelo bears in the North.