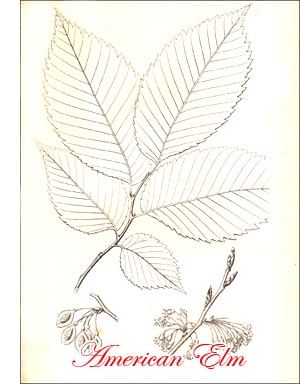

White Elm or American Elm Tree

White Elm, American Elm (Ulmus Americana, Linn.)A tall, graceful, wide-spreading tree, 75 to 125 feet high, usually of symmetrical, vase shape, with slender limbs and pendulous twigs. Bark dark or light grey, rough, coarsely ridged; branches grey; twigs reddish brown. Wood reddish brown, with pale sap wood; coarse, hard, heavy, strong, cross grained, difficult to split, durable in water and soil. Buds acute, flattened, smooth; Power buds lateral, large. Leaves alternate, 2 to 6 inches long, obovate, doubly serrate, acuminate, unequal at base; smooth above when mature; ribs parallel. Flowers, March, before leaves, on slender, drooping pedicels in umbel-like clusters, perfect, greenish red, inconspicuous. Fruit, May, smooth, oval with thin ciliated circular wing, notched above to the nutlet. Preferred habitat, rich, moist soil. Distribution, Newfoundland to Florida; west to Rocky Mountains. Uses: Favourite shade and ornamental tree. Wood used for hubs, saddle trees, barrels and kegs, flooring, in boat and shipbuilding, flumes and piles. Indians used bark for canoes and ropes.

White Elm, American Elm (Ulmus Americana, Linn.)A tall, graceful, wide-spreading tree, 75 to 125 feet high, usually of symmetrical, vase shape, with slender limbs and pendulous twigs. Bark dark or light grey, rough, coarsely ridged; branches grey; twigs reddish brown. Wood reddish brown, with pale sap wood; coarse, hard, heavy, strong, cross grained, difficult to split, durable in water and soil. Buds acute, flattened, smooth; Power buds lateral, large. Leaves alternate, 2 to 6 inches long, obovate, doubly serrate, acuminate, unequal at base; smooth above when mature; ribs parallel. Flowers, March, before leaves, on slender, drooping pedicels in umbel-like clusters, perfect, greenish red, inconspicuous. Fruit, May, smooth, oval with thin ciliated circular wing, notched above to the nutlet. Preferred habitat, rich, moist soil. Distribution, Newfoundland to Florida; west to Rocky Mountains. Uses: Favourite shade and ornamental tree. Wood used for hubs, saddle trees, barrels and kegs, flooring, in boat and shipbuilding, flumes and piles. Indians used bark for canoes and ropes.Up and down New England the trolley cars ply in a maze of systems that becomes more complex every year. Buzzing like insistent and inquisitive bumblebees, they awaken the sleepiest hamlet, haling its inhabitants to the cities and unloading weary, city-bound mortals in the green country. They stir the torpid, stagnant pool of existence; they wake the old nomadic cravings of the primitive race. The most indignant farmer or villager, once he gets thoroughly awake, ceases to grumble; for his feet of clay the trolley gives him the wings of a bird.

I am not an idolater, I hope, and I would chiefly scorn to worship the almighty dollar. But the vast extent of picturesque country one can see for this sum by trolley in New England fills me with a surprise akin to awe.

The striking ornament of New England landscapes is the American elm. The countryside abounds with splendid specimens. They are the pride of cities and villages. Down fine old avenues arched over with their mighty arms the trolley cars take their noisy way.- The Westerner stands astonished at the giant size of these trees, and wonders why he cannot match them at home. It is largely a matter of time. In the early days our ancestors took up the trees from the woods and planted them by their roadsides and about their dwellings. Memories of elms at homes-the beautiful Ulmus campestris in England and on the Continent-guided their choice. Trees twenty years old were transplanted with safety, for this elm has fibrous roots that keep near the surface of the ground. Then the busy home-makers let the trees alone. They had no time to prune and cultivate. The trees needed no such attention. The roots ranged freely in the virgin soil. The spreading tops were self-pruning-the strong limbs choked the weak ones, keeping an open, symmetrical head. Every year added to the tree's stature. It is a race of giants now, against whom insect hosts have come-the tussock moths, the elm-leaf beetle and the brown tall. No wonder the people have made the fight their own.

The elm is familiar to everybody-its vase-like form is in sight whenever we look out of a window. I t grows everywhere east of the Rocky Mountains, and ignorance of it is a mark of indifference or stupidity. No village of any pride but plants it freely as a street tree.

The Etruscan vase form-a base gradually flaring to a round dome-is most common. The trunk soon divides into three or four main limbs with slight but constant divergence as they rise. Their branches follow their example. The divisions are drawn downward by their increasing weight, and the extremities are pendulous, sweeping out and down with loads of foliage, luxuriant, but never heavy looking or ungraceful.

There are narrower elm forms: tall trunks whose limbs form a brush at the top, not unlike a feather duster. Such trees often replace lost outer limbs by a multitude of short leafy twigs, covering the trunks with foliage, thus forming what are known as "feathered elms."

The "oak-tree form"-wider and broader than the vase form-reminds one of the ample crown of an oak. But only the outline is suggestive. The limbs are curved, never angular and tortuous like the oak. Grace rather than strength is invariably the expression of the American elm. In good soil the terminal shoots attain great length, and it is not unusual Lo see an elm of vase shape with the droop of a weeping willow.

The leaves of the elm are two-ranked, the twigs plume-like. Every chink is filled with a leaf. Break off a branch that faces the sun, and you will be astonished at the twisting and contriving of the leaves, to present an unbroken surface of green. This is known as a "leaf mosaic," and is by no means confined to elms. Any roadside thicket shows the same habit in all its species.

I think, with all due regard for its summer luxuriance, and the grace of its framework in winter, the greatest charm invests the elm of the roadside in the first warm days of spring. The swelling buds are full of promise. A flush of purple overspreads the tree, while snow yet covers the ground. A tremendous "fall of leaves" ensues-for the tiny leaf scales that enclose the elm flowers are but leaves in miniature. The elms are in blossom; they are among the first in the flower procession that silently passes till the witch hazel brings up the rear in October. Then come the little green seeds, winged for flight. These ripen and are scattered before the leaves are open, and the growth of the season's shoots really begins. How much they miss who never see the elms in flower and fruit!

American Elm Tree picture