Red Clover

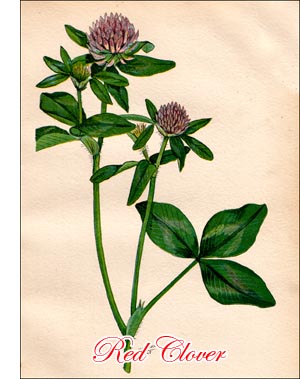

RED CLOVER (Trifolium pratense L.)

RED CLOVER (Trifolium pratense L.)Botanical description:

Red Clover is mainly biennial. The year the seed germinates, only short leaves and stems are produced and no flowers. The second year the flowers are developed and the seed formed, and after ripening the seed the plant dies. As with most biennial plants, the root is a taproot; that is, the single main root gradually tapers downward and produces numerous side branches. On these are developed the small, rounded or egg-shaped nodules which contain the bacteria necessary for the proper development of the plant.From the upper end of the taproot, which is somewhat enlarged and generally known as the crown, are formed more or less numerous buds which develop into leafy stems. These as a rule are from one-half to two feet high, strictly upright or ascending from a decumbent base, the latter being the normal growth of stems developed from the outer margin of the crown.

The stems are generally branched above the middle and the leaves are single at each joint. The three leaflets of which each leaf consists are oblong or egg-shaped and usually marked with a white spot of varying size and shape. The stipules attached to the base of the leaf stalk are triangular at the base and suddenly contracted into an awnlike point.

This peculiar shape is a characteristic by which Red Clover can be readily distinguished from Zigzag Clover (Tri-folium medium L.), which it closely resembles and is often confused with. The stipules of Zigzag Clover are narrow throughout. The Red Clover flowers are in a dense head, which is about an inch in diameter when fully developed. They vary from bright red to purple but are sometimes white.

Biology of flower:

If Red Clover is isolated during flowering time, so that no insects can visit the blooms, no seeds will be formed, as it depends upon insects to transport the pollen from one flower to another. Bumble bees, which visit the flowers in order to secure the nectar, are especially active in this transportation. The blossoms of Red Clover are peculiarly sensitive; when a bumble bee in search of honey forces its proboscis down and touches the lower parts of a flower, such a touch, if the flower is fully developed, makes the stamens and pistil protrude from the interior of the blossom into the open air.The bending of the stamens and pistil brings their upper ends into close contact with the body of the insect, which thus becomes powdered with pollen from the stamens. The pistil protrudes a little beyond the stamens. This might seem an insignificant fact, but it means that the pistil has a better chance to come in contact with the pollen from other plants, already deposited on the body of the insect, than to come in contact with the pollen of its own flower. As the insect travels from one plant to another, carrying pollen from different individuals, the pistils of one are apt to be fertilized by pollen from another. Such cross-fertilization must, in fact, take place before seed can be developed. In other words, Red Clover is completely self-sterile. The pollen is unable to fertilize the pistils of the plant on which it is produced.

As a rule, the insect carries enough pollen from different individuals to give the pistils an opportunity to be powdered from other plants. There is, however, a chance that a single visit from one insect would be insufficient. To provide a greater opportunity for every flower to be fertilized, nature has made it possible to have each Red Clover blossom visited by insects many times. In Alfalfa each flower has only one chance to be fertilized, as the stamens and the pistil, after the explosion of the flower, do not return to their original positions. A Red Clover blossom has many chances, as the pistil and stamens protrude for only an instant, after which they move back to their original positions. Their sensibility is not lost after the first visit of an insect; a second or third visit will have the same effect, and the chances of the pistil being properly fertilized will last as long as it remains in a condition to receive the pollen.

Bumble bees are the only insects, with the exception of some butterflies, with a proboscis long enough to reach the nectar at the bottom of the flower tube. As is well known by bee-keepers, the ordinary honey bee is not able to gather honey from Red Clover, its proboscis being far too short. In spite of this, however, the ordinary honey bee is of considerable importance in the fertilization of Red Clover. Though it cannot reach the honey, it can reach the pollen, and when securing this for bee bread it comes in contact with the pistil and thus has an opportunity to assist fertilization.

The result of the fertilization of the flower is the development of a small, straight pod containing one seed. When fully ripe this is released by the falling off of the upper caplike part of the pod.

Red Clover and all other species of the genus Trifolium behave in a rather peculiar way after flowering. Their flowers do not fall off but remain withered on the head during the whole season, giving the ripened heads their characteristic brown appearance. This peculiarity makes it easy to distinguish the genus Trifolium from the genus Medico go, the flowers of the latter not being persistent. The pods of Alfalfa and other species of Medicago are exposed while ripening, whereas the pods of Red Clover and other species of Trifolium are not visible.

Geographical distribution:

Red Clover is a native of Europe, southwestern Asia, parts of Siberia and northern Africa.History:

It was introduced into culture comparatively late. In Italy and Spain its cultivation was established during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It was introduced into Holland from Spain during the sixteenth century and from there it made its way to England during the first half of the seventeenth, the English name being derived from the Dutch "Klafver." It was introduced into North America during the last decennium of the eighteenth century.Cultural conditions:

Being a resident of the temperate zone, Red Clover succeeds best where the summers are not too hot nor the winters too severe. Although the roots go rather deep, the plant is injured by long and continuous drought. It needs sufficient rain during the growing period to enable it to flourish during the whole season. As Red Clover is rather cosmopolitan, a great number of varieties, adapted to different climates, have been developed. The suitability of a variety for a northern climate like that of Canada depends to a great extent upon its hardiness. Chilean Red Clover or other varieties originating in countries with a mild climate are invariably killed by the Canadian winter, except in the southern parts of the country. It is therefore important to secure seed of northern origin. If possible, Canadian grown seed should be obtained because as a rule homegrown seed gives the best results.Soil:

Red Clover can be successfully grown on many kinds of soil, the most suitable being clay loams with a certain amount of lime and plenty of organic matter. Sandy loams also give good returns, especially on limestone foundation; but generally speaking, Red Clover prefers the heavier soils. It can be grown even on stiff clay, provided the subsoil is open. For its proper development Red Clover, like Alfalfa, depends a good deal upon the subsoil. This must be open and well-drained. Stagnant water near or on the surface is decidedly injurious. Water-soaked soil excludes the air necessary for the respiration of the roots and is in a bad physical condition to meet the alternate thawing and freezing of early spring. As is well known, water expands when changing into ice, and if the surface soil contains an abundance of water it will consequently expand when freezing. The overground parts of the plants will be lifted up with the freezing soil. As the lower roots are anchored in the subsoil and therefore unable to follow the upward movement, they will be stretched and sometimes broken. The disastrous effects of alternate freezing and thawing make it evident that one of the first conditions of successful clover growing is well-drained soil.Habits of growth:

Being a biennial, Red Clover devotes the first season's growth to the development of its root system and the accumulation of strength to meet the winter's hardships. It therefore produces a strong tap root, which, if soil and weather are favourable, penetrates to a considerable depth. The overground parts of the plants consist at first of only a few, short, upright stems which carry leaves but no flowers. Later in the season, short leafy shoots are developed which generally lie flat on the ground and are known as the winter tuft. At the same time the tap root begins to contract until its original length is reduced by more than ten per cent. As the end of the root is firmly anchored in the ground, the result is that the overground parts of the plant are pulled down. This process,_ which has been observed in other plants such as carrots and parsnips, is evidently meant to bring the stems and leaves into close contact with the ground where they are best protected against frost and wind. Early in the spring of the second year the branches of the winter tuft develop into flower-bearing stems, which, if not cut or pastured, produce seed and late in the fall die. The great mass of clover plants are thus biennial. Red Clover types exist, however, which show a decided tendency to live longer, especially if the plants are kept from seeding by continual cutting or pasturing. The best known of these perennial types is Mammoth Clover.Agricultural value:

No forage plant has been so important to agriculture as has Red Clover. This is due not only to its high feeding value, which is surpassed by few plants, but also to its service as a fertilizer and improver of soil texture. No other leguminous fodder plant is equal to it for these two purposes.Fodder:

Red Clover has its highest feeding value when in full bloom and should be cut for hay before the heads begin to turn brown. If cut late, the stems become woody, lose their palatability and the general value is considerably lessened. The quality of the hay depends to a great extent on the way it is cured. Careless handling causes the leaves to shatter. Exposure to rain or heavy dew discolours the hay, dispels its fine aroma and reduces its nutritive value. Over exposure to sunshine also reduces its feeding value. In curing Red Clover hay methods should therefore be employed by which the drying is done as much as possible by the wind.Pasture:

As a pasture plant, Red Clover is no t surpassed by any other legume. It is relished by all kinds of farm animals. On account of the tenderness of the young plants and the necessity to have them start the winter in good condition, it is not advisable in the Prairie Provinces to pasture Red Clover the same year it is sown. In some parts of Ontario, where it may grow rather rank the latter part of the first year, the field is usually pastured: to what extent depends upon conditions. Grazing too late in the fall or pasturing too close by sheep is apt to reduce the succeeding crop. Grazing the second year may begin early in the spring and continue until late in the fall.When cattle and sheep are turned into a field of Red Clover, there is always danger of bloating, especially if it is wet with dew and the animals start grazing on empty stomachs.

Sowing for hay and pasture:

In Ontario Red Clover is always sown with a nurse crop. Tests at the experimental farms of Manitoba and Saskatchewan, particularly at Indian Head, indicate that in the Prairie Provinces a nurse crop should not be used. In a dry climate or on dry soils it acts as a robber rather than as a nurse in depriving the young plants of moisture. The result is that the plants are weak at the beginning of the winter and are more liable to be killed by the frost. When sown alone, ten to twelve pounds of good seed should be used to the acre.Red Clover picture

Red Clover seed