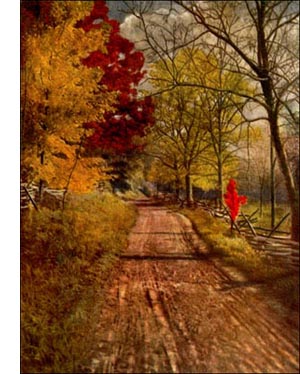

Red Mulberry Tree

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra, Linn.)-Large tree, 60 to 70 feet high, with dense, round head, fibrous roots and milky juice. Bark light brown, reddish, dividing into scaly plates; branches reddish; twigs grey, downy. Wood orange yellow, light, coarse grained, soft, weak, very durable in soil. Buds ovate, blunt, small. Leaves alternate, variable in form, 3 to 5 inches long, broad, acuminate, serrate, very veiny, often lobed and palmately veined; usually rough, blue-green above, pale and pubescent beneath, yellow in early autumn; petioles stout, long. Flowers monoecious or dioecious, variable, in stalked, axillary spikes, staminate flowers with flat, 4-lobed calyx and 4 incurved stamens that spread suddenly and lie flat on calyx, forming a cross as they mature; pistillate flower, a vase-shaped, 4-lobed calyx, with two stigmas protruding. Fruit fleshy calyx lobes, surrounding single seed; whole spike unites to form an aggregate fruit, sweet, juicy, dark purplish red. Preferred habitat, rich well-drained soil. Distribution, western Massachusetts to southern Ontario, Michigan, Nebraska, Kansas; south to Florida and Texas. Uses: Wood used in cooperage and for fencing. A worthy tree for ornament, but rarely planted.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra, Linn.)-Large tree, 60 to 70 feet high, with dense, round head, fibrous roots and milky juice. Bark light brown, reddish, dividing into scaly plates; branches reddish; twigs grey, downy. Wood orange yellow, light, coarse grained, soft, weak, very durable in soil. Buds ovate, blunt, small. Leaves alternate, variable in form, 3 to 5 inches long, broad, acuminate, serrate, very veiny, often lobed and palmately veined; usually rough, blue-green above, pale and pubescent beneath, yellow in early autumn; petioles stout, long. Flowers monoecious or dioecious, variable, in stalked, axillary spikes, staminate flowers with flat, 4-lobed calyx and 4 incurved stamens that spread suddenly and lie flat on calyx, forming a cross as they mature; pistillate flower, a vase-shaped, 4-lobed calyx, with two stigmas protruding. Fruit fleshy calyx lobes, surrounding single seed; whole spike unites to form an aggregate fruit, sweet, juicy, dark purplish red. Preferred habitat, rich well-drained soil. Distribution, western Massachusetts to southern Ontario, Michigan, Nebraska, Kansas; south to Florida and Texas. Uses: Wood used in cooperage and for fencing. A worthy tree for ornament, but rarely planted.The red mulberry, discovered in Virginia in great abundance, inflamed the minds of early colonists who counted it one of the chief resources of the colony. A tree "apt to feede Silke-worms to make silke" promised truly "a commoditie not meanely profitable" in a new colony-made up of gentlemen. A Frenchman, reporting the abundance of these trees, mentions "some so large that one tree contains as many leaves as will feed Silke-wormes that will make as much silk as may be worth five pounds sterling money." But their sanguine hopes were not realised. The red mulberry is no substitute for the white species. Silk culture is still an Old World industry, even though white mulberries grow in this country.

Indians discovered that ropes and a coarse cloth could be woven out of the bast fibre of mulberry bark. The berries have some medicinal properties, and are eagerly devoured by hogs and poultry. The chief value of the tree lies in the durability of its wood, which commends it to the boatbuilder, the cooper, and to the man with fences to build.

One of the mulberry's chief characteristics is its tenacity to life. Its seeds readily germinate, and cuttings strike quickly, whether from roots or stems. Evelyn's instructions for propagating the European mulberry by cuttings are quaint and worth hearing. "They will root infallibly, especially if you twist the old wood a little or at least hack it; though some slit the foot, inserting a stone or grain of an oat to suckle and entertain the plant with moisture."