Wild Crab Apple Tree

Wild Crab Apple (Malus coronaria, Mill.)-A low, bushy tree, with thorny angular twigs, rarely 30 feet high. Bark reddish brown, scaly. Wood heavy, fine grained, weak, reddish brown. Buds small, blunt, bright red. Leaves ovate or triangular, 3 to 4 inches long, half as broad, velvety beneath, blunt pointed, sharply serrate, often lobed near base; petioles 1 1/2 to 2 inches long.

Wild Crab Apple (Malus coronaria, Mill.)-A low, bushy tree, with thorny angular twigs, rarely 30 feet high. Bark reddish brown, scaly. Wood heavy, fine grained, weak, reddish brown. Buds small, blunt, bright red. Leaves ovate or triangular, 3 to 4 inches long, half as broad, velvety beneath, blunt pointed, sharply serrate, often lobed near base; petioles 1 1/2 to 2 inches long. Flowers May to June, after the leaves, in 5 to 6 flowered umbels, perfect, white to deep pink, spicy, fragrant 1 to 2 inches across. Fruit flattened, yellow, 1 inch in diameter; flesh hard, sour. September. Preferred habitat, upland woods, in moist, rich soil. Distribution, Ontario to Minnesota; south along Alleghanies to Alabama; Nebraska to eastern Texas; New York to South Carolina. Uses: An ornamental, flowering tree. Fruit made into jellies and preserves. Wood used for levers, tool handles, etc.

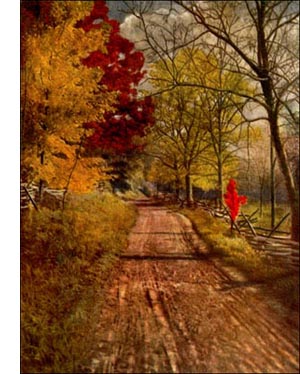

The wild, sweet-scented crab apple! The bare mention of its name is enough to make the heart leap up, though spring be months away, and barriers of brick hem us in. In the corner of the back pasture stands a clump of these trees, huddled together like cattle. Their flat, matteded tops reach out sidewise until the stubby limbs of neighbouring trees meet. lt would not occur to anyone to call them handsome trees.

But wait! The twigs silver over with young foliage, then coral buds appear, thickly sprinkling the green leaves. Now all their asperity is softened, and a great burst of rose-coloured bloom overspreads the treetops and fills the air with perfume. It is not mere sweetness, but an exquisite; spicy, stimulating fragrance that belongs only to wild crab-apple flowers. Linnaeus probably never saw more than dried specimen, but he named this tree most Worthily, coronaria, "fit for crowns and garlands."

Break off an armful of these blossoming twigs and take them home. They will never be missed. Be thankful that your friends in distant parts of the country may share your pleasure, for though this particular species does not cover the whole United States, yet there is a wild crab apple for each region.

In the fall the tree is covered with hard little yellow apples. They have a delightful fragrance, but they are neither sweet nor mellow. Take a few home and make them into jelly. Then you will understand why the early settlers gathered them for winter use. The jelly has a wild tang in it, an indescribable piquancy of flavour as different from common apple jelly as the flowers are in their way more charming than ordinary apple blossoms. It is the rare gamy taste of a primitive apple.

Well-meaning horticulturists have tried what they could do toward domesticating this Malus coronaria. The effort has not been a success. The fruit remains acerb and hard; the tree declines to be "ameliorated" for the good of mankind. Isn't it, after all, a gratuitous office? Do we not need our wild crab apple just as it is, as much as we need more kinds of orchard trees? How spirited and fine is its resistance!

It seems as if this wayward beauty of our woodside thickets considered that the best way to serve mankind was to keep inviolate those charms that set it apart from other trees and make its remotest haunt the Mecca of eager pilgrims every spring.

The wild crab apple is not a tree to plant by itself in park or garden. Plant it in companies on the edge of woods, or in obscure and ugly fence corners, where there is a background, or where, at least, each tree can lose its individuality in the mass. Now, go away and let them alone. They do not need mulching nor pruning. Let them gang their ain gait, and in a few years you will have a crab-apple thicket. You will also have succeeded in bringing home with these trees something of the spirit of the wild woods where you found them.