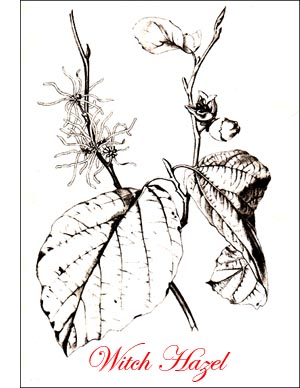

Witch Hazel Tree

Genus HAMAMELIS, Linn.

Genus HAMAMELIS, Linn.The Witch Hazel (Hamamelis Virginiana, Linn.)-A small tree, or usually a stout shrub, rarely 25 feet high. Bark light brown, scaly or smooth. Wood close grained, hard, heavy, brownish red, with thick, white sap wood. Buds sickle shaped, pale brown, hairy, enclosed in leafy stipules. Leaves alternate, unsymmetrical, strongly veined, oval or obovate, wavy margined, or coarsely serrate, 4 to 6 inches long, rusty-hairy at first, yellow in autumn, often hanging all winter.

Flowers in autumn, clustered, greenish, with 4 yellow ribbon-like petals. Fruits ripe in autumn, a 2-beaked, 2-celled, woody capsule that opens explosively; seeds, 2, black, shiny. Preferred habitat, low, rich soil or rocky stream banks. Distribution, Nova Scotia to Nebraska, south to Florida and Eastern Texas. Uses: Valuable ornamental. Bark, twigs and leaves used in making extract for rubbing bruises.

There is nothing in the forest west of the Mississippi Valley that quite compensates the Easterner for the absence of the witch hazel, familiar to every lover of the woods in his half of the continent. Not that it is a very important tree, in any practical sense, but it is an integral and familiar part of the woods it frequents, filling in the bare places with undergrowth and exhibiting interesting and unusual habits. It is the most inconspicuous tree in the woods in spring.

Its opening leaves are coated with rusty hairs, which the botanist finds interesting because they branch into star-shaped tops. But to the casual observer these leaves look old and dingy, compared with the bright green foliage about. And no sign of bloom adorns the witch hazel while the impressive flower pageant is passing. Only the curious, lifting a branch and looking in the axils of last year's leaves, will see little curved stems each capped by a cluster of green-grey cups, dull from their winter's contact with the elements. On the newer shoots, and at the bases of leafy side spurs cluster tiny green balls no larger than pin heads. A few brown pods, dry and empty, drop to the ground, as the wind shakes the tree.

All through the summer the witch hazel tells its secrets only to the thoughtful and keen-eyed observer. The side branches send out twigs of varying lengths. The longest and thriftiest of these are near the extremity of the limb, where the best light is, and the most room. Here the broad leaves spread their faces toward the sun, and under them little green buttons assert themselves, rending apart the cups that easily contained them in spring.

Every tree has its supreme moment of beauty. This usually comes when the foliage is in its prime, or when the flower buds 'burst in spring. The witch hazel is an exception to all rules. When the crisp autumnal atmosphere warns all plant life to get ready for winter the witch hazel trees put a new construction on the message. As if by magic, all up and down through the woods they burst into bloom, each flower bravely flaunting four delicate petals like tiny yellow streamers. The woods are fairly sprinkled with these starry, gold-thread blossoms, and a rare fragrance breathes upon the languid October air. The ripening leaves second and intensify the colour of the flowers, which often thickly fringe the outstretched twigs, and cover up the green buttons.

Ah! here is another surprise the witch hazel has to offer. These buttons, so precious to the tree, contain the seeds developed from the flowers that bloomed last year. It has taken a full year to ripen them. Each pod has two cells, with a shiny black seed prisoner in each. The frost gives the signal, and the pods fly open with a snap, freeing the seeds, and ejecting them with surprising force. Dry, cold weather will discharge the whole seed crop in a few days. They shoot in every direction, and to a distance sometimes of twenty feet from the foot of the tree. But warm, wet weather delays their game. The pods are close and glum. There is no spring in them till they are dry again.

It is a far cry from March to October; from furry tassels of blossoming aspens and willows to the witch hazel in its yellow blossoms bringing up the rear in the great annual procession of the flowers. In fact, the witch hazel practically bridges the chasm of winter, for at no time does the cold cause all the flowers to fall. Their yellow petals curl up like shavings; but they often stay till spring.

A witch in old days was a person who did or said things not conventional. Our witch hazel has defied the ancient laws of the calendar-a very dreadful thing! So it comes honestly by its name; and one is inclined to ignore the accepted etymology that the word "witch," or "wych," in Old English, means "weak," and refers to the sprawling habit of the tree. Surely the observer cannot miss seeing little weazen witch faces grinning at him from all possible angles of the tree, their yellow cap strings flying in the wind, as if in defiance of the rumour that the days of witchcraft are past.

The English "wych hazel" is an elm. In the mining regions it would be counted the height of folly to sink a shaft without first determining with a hazel wand where the rich veins of coal or metal are. No more would one think of digging a well until the same divining rod pointed to the hidden springs. Our American witch hazel is credited with all the occult powers of the Old World tree from which it gets its name. In hamlets and country neighbourhoods not too close to the currents of modern life we may still meet old fellows who can "water witch," and a goodly number of neighbours who believe in his powers.

Billy Thompson's well goes dry and he sends in haste for Old Andy. Promptly, but with no undignified haste, the old man goes out into the woods that join his "clearin'." He chooses a forked twig whose Y stands north and south, for the rising and setting suns must have sent their rays through its prongs as it grew. Carefully the leaves are removed, as they drive to Billy's place, where the whole family and a neighbour or two await them. A solemnity settles on the company as the supple twig is grasped by its two forks, thumbs out, knuckles down, and the stem of the Y is thrust forward. Holding it as rigid as his trembling old hands are able, Andy paces with dignity over the ground that Billy has chosen as a convenient site for the new pump. He shakes his head as the stubborn wand keeps its position. "There's no use diggin' thar." Billy is disappointed, but convinced.

Old Andy stumbles along and the wand points downward. It is most emphatic. Back he comes across the same spot, and down goes the wand again. He moves away-even to the other side of the barn-then returns and the sign is repeated over the exact spot indicated before. "D'ye see his wrist move?" asks a doubter, nudging his neighbour, and speaking under his breath. But it is not a time for levity. All eyes are on the seer who announces with proper dignity: "Thar's the place, Billy. The signs is plain. You'll git a good spring-fed well if you go deep enough." And nobody has the hardihood to dispute his word.

Witch Hazel picture